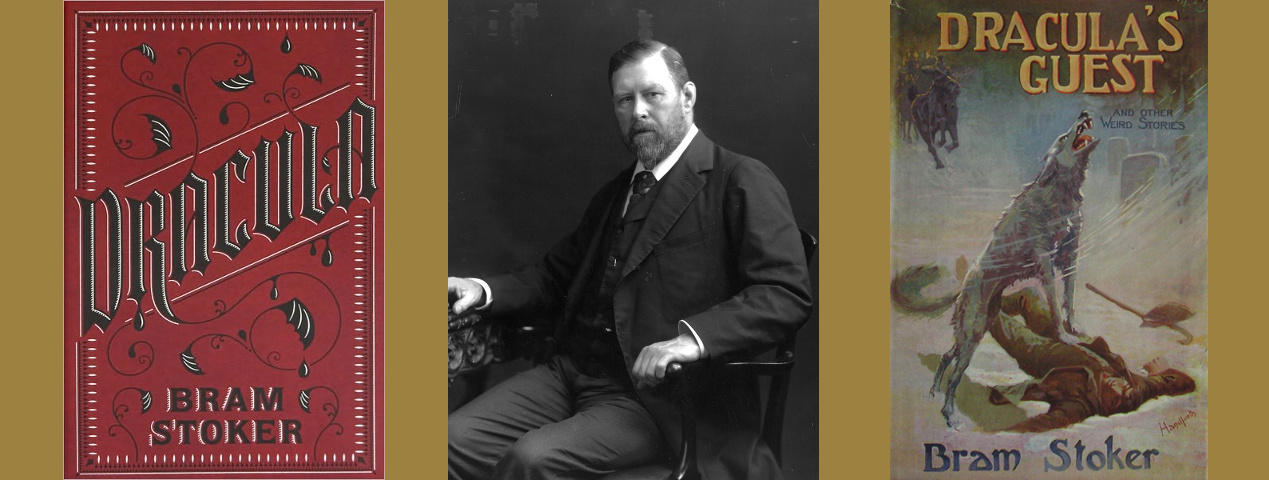

In January 2017, it became big news around the world, at least in comparison with other literary news, that Bram Stoker's "lost" version of

Dracula had been discovered in Iceland, where it had lain forgotten for over 100 years. It was now published in English:

Powers of Darkness: The Lost Version of Dracula. This was an Icelandic translation of

Dracula, originally published in the magazine

Fjallkonan from January 13, 1900 to March 29, 1901, under the title

Makt myrkranna ("Powers of Darkness" in English). It was then published in book form in 1901. The Icelandic translator was said to be the author and publicist Jóhann Valdimar Ásmundsson (1852-1902). However, this was a drastically different version of the 1897 classic edition of

Dracula.

It was the Dutch art historian and Dracula researcher Hans Corneel de Roos who made the discovery. Together with the internationally renowned experts Dacre Stoker (related to Bram) and John Edgar Browning, he compiled the English edition. De Roos, Browning and Dacre Stoker found that

Makt myrkranna showed obvious signs of having been written in collaboration with Bram Stoker himself, or had been adapted from an early draft by Stoker of the classic vampire novel. David J. Skal also advocated this in his great biography of Stoker,

Something in the Blood (2016).

Makt myrkranna is almost half the length of the 1897

Dracula, although the opening section with Harker's visit and captivity in Dracula's castle is significantly longer than the corresponding section in the 1897 version. The rest consists of little more than an abstract of the plot, in large parts written in a sketchy manner. On the other hand, it contains several of the ingredients that Stoker planned to use in his novel, but which were then removed in the final version. The discovery of this "lost" version led to detailed speculations: How could a draft of

Dracula have ended up in Iceland, and who was the intermediary link between Stoker or his draft of the novel, and the editor Valdimar Ásmundsson?

As soon as I heard of the English edition, I remembered that the first Swedish translation of

Dracula had the same title in my native language:

Mörkrets makter. When I looked it up in the online database at the National Library of Sweden, it appeared that it was published as a serial in the newspapers

Dagen and

Aftonbladets Halfvecko-Upplaga, beginning in the summer and autumn of 1899 – the year

before the Icelandic edition began to be published. Even this was remarkable enough. I gave my colleague Jan Reimer the duty to order the edition and send me copies of the pages, because I live in Bangkok.

It was a jackpot.

Mörkrets makter is far more than just the original text of Ásmundsson's translation. The version published in

Dagen is a full-scale novel without abridgements and sketchy parts – and almost twice as long as the 1897

Dracula! It consists of 1,625,800 characters including spaces, compared to

Dracula's 830,000 characters. Here are also several scenes and characters that are not even mentioned in the Icelandic edition, and even less in the classic version.

The novel was serialized in the newspaper

Dagen ("The Day") from June 10, 1899 to February 7, 1900, as "Powers of Darkness: Novel by Bram Stoker: Swedish Adaptation for

Dagen by A–e." Simultaneously, it was published in

Aftonbladets Halfvecko-Upplaga (a special edition of the tabloid

Aftonbladet, published twice a week in the provinces) from August 16, 1899 to March 31, 1900.

Aftonbladet with its half-week edition and

Dagen had the same editor-in-chief, Harald Sohlman, and partly the same editorial staff.

The texts are identical until the end of the first section, when Harker decides to escape from Draculitz's castle using a sheet as a rope. Then in

Aftonbladet, the abridged and sketchy style begins, which later appears in

Makt myrkranna. However, the Icelandic version has been abridged even further. For example,

Aftonbladet's version still has Renfield as an important minor character, while he is completely removed in

Makt myrkranna.

It is a bit ironic. So much academic effort and research have been wasted on an Icelandic text, which is only a pale abridgement of an already abridged Swedish version, based on an original text published in the newspaper

Dagen around the turn of the century 1900. It would not have been very hard to find the Swedish original text, if they had only paid online visits to more national libraries in Scandinavia and searched their databases. When the English-language newspaper

Iceland Monitor wrote about the discovery of the Swedish version on March 6, 2017, Professor Guðni Elísson explained that literary scholars in Iceland had long suspected that

Makt myrkranna is just a translation from another Scandinavian language, and not an Icelandic original text – the idea already existed.

However, there is no reason to be mean. After all, it is impossible to deny that Hans Corneel de Roos and his team were on the right track – and that the track is both fascinating and invaluable for the research into the history and background of

Dracula.

The version in

Aftonbladets Halfvecko-Upplaga was never reprinted in Sweden. The full version in

Dagen was republished a second and last time in

Tip-Top No. 40, 1916 to No. 4, 1918, a cheap weekly magazine for pleasure reading. There it was presented as "Novel by Bram Stoker. Swedish Adaptation for

Tip-Top by A–e". But with the exception of details such as removed dashes and a few new word choices, as well as a few deleted sentences and paragraphs, the text is identical to the text in

Dagen.

In

Dagen and

Aftonbladets Halfvecko-Upplaga, the novel was provided with unsigned illustrations. Usually they only show people who talk to each other and are often not very well-made, but some of the more interesting examples can be found in this article.

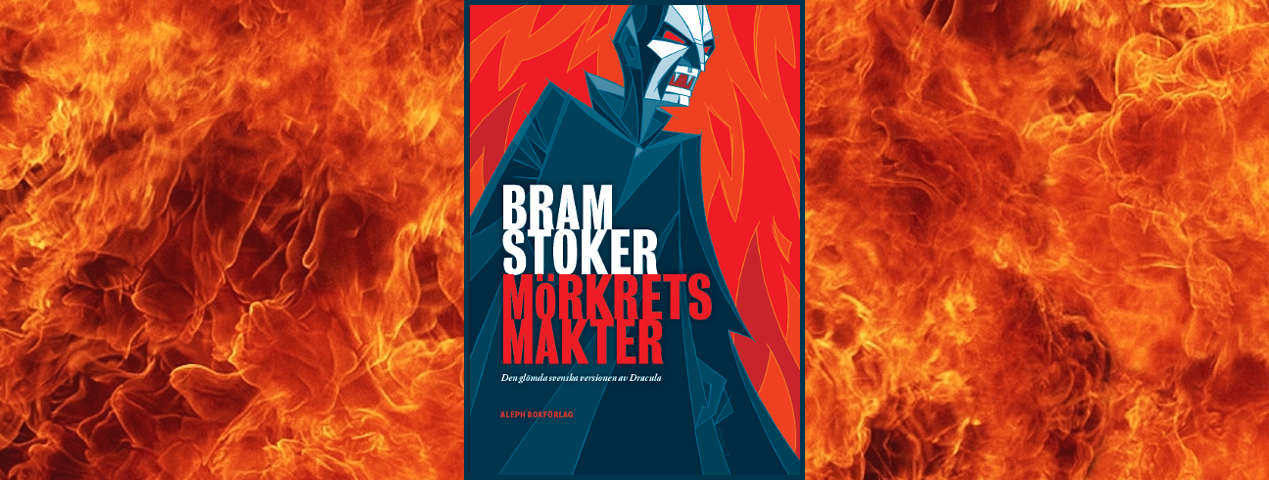

The Swedish small press company Aleph Bokförlag published the full text of

Mörkrets makter in October 2017 with a preface by John Edgar Browning. And the opinion remains: "... among the most important discoveries in Dracula's long history," as Browning writes.

POWERS OF DARKNESS

Mörkrets makter was not entirely unknown in Sweden, as noted in Sam J. Lundwall's standard reference work

Bibliografi över science fiction och fantasy ("Bibliography of Science Fiction and Fantasy," which contains only Swedish titles). Obviously, however, no literary scholar has noticed how drastically this version differs from the

Dracula of 1897, and even less has understood the importance of it. Here, it is not only the vampire race Dracula wants to spread across the world, he is also conspiring with politicians and other men of power around the world to introduce a new world order based on a kind of racial biology and outright fascist ideas about the natural right to rule inherited by "the strong" individuals. Count Dracula – or Draculitz, as he is called here – views the vampire race as the next step in the evolution of humanity, a new "master race" as Hitler soon was to call it.

Mörkrets makter can in parts be read as a satire of – and a warning for – the Social Darwinist theories that flourished at the turn of the century 1900. In a fascinating dark way, the novel foretells the disasters which Nazism and Fascism would bring into the world in the 1930s and 1940s.

Toward the end, the novel plays strongly on the

fin de siècle pessimism of the 1890s and the troubled state of the Western world. Numerous tensions in national and international politics laid the foundation for World War I and led indirectly to World War II. Dr. Seward reflects on this when he is reading a tabloid paper:

By the way, the telegram section of the newspaper announces several strange news – lunatic behavior and deadly riots, organized by anti-Semites, in both Russia and Galicia as well as southern France – plundered stores, slain people – general insecurity of life and property – and the most fabulous tall tales about "ritual murders," abducted children and other unspeakable crimes, all of which is ascribed in earnestness to the poor Jews, while influential newspapers are instigating an all-encompassing extermination war against the "Israelites." You would think this is in the midst of the Dark Ages! [...] Now, once again, it seems that a so-called "Orlean" conspiracy is tracked down – while at the same time the free Republicans in France are celebrating with exaltation the exponent of slavery and despotism in the East [...] It is a strange time in which we live, that is sure and true. – – – Sometimes it seems to me as if all the insane fantasies, all the crazy ideas, the whole world of crazed and scattered notions, into which I, as a madhouse doctor, for years have been forced to enter in the care of my poor patients, now begin to take shape and form and gain practice in the course of the world's major events and tendency.

The "so-called 'Orlean' conspiracy" refers to more or less well-founded rumors of a planned military coup against France, which in 1898-99 surrounded the pretender to the throne of France: Louis Philippe Robert, Duc d’Orléans (1869-1926). A detail like this shows that at least parts of the adaptation was done after

Dracula was published in 1897.

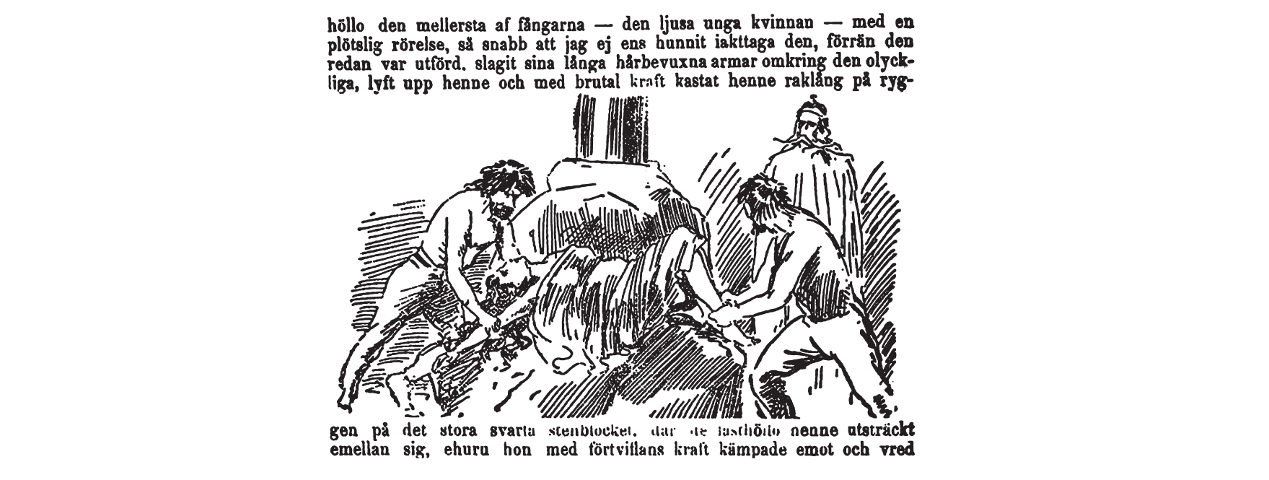

Mörkrets makter also satirizes the zeitgeist with its craze for occultism and newly constructed religions, where both the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and Madame Blavatsky's Theosophy were of significance for the upper classes in England. Deepest below the castle, chiseled out of the cliff itself, are cavities where Count Draculitz as a high priest practices a disgusting pagan religion with human sacrifices, worshiped by beastly degenerated cave people; a religion that he now plans to spread across the world together with his other beliefs.

BRAM STOKER AND THE DRACULA OF THE DAY

During his lifetime, the Irishman Abraham "Bram" Stoker (1847-1912) was known as the assistant and constant companion of the famous actor Sir Henry Irving. He also served as the head of the Lyceum Theatre in London with its grand building, in which Irving performed when he was not on tour. Stoker's writing was a spare-time occupation for him during this time, but he was forced into the role of professional writer after 1905 when Irving died and his employment at the Lyceum Theatre ended. Stoker's finances suffered and periodically he needed medical care because of overwork. Towards the end of his life he is believed to have suffered several strokes. The cause of his death is obscure, but David J. Skal argues strongly for the controversial opinion that Stoker died from syphilis infecting the nervous system (and thus also caused what has been interpreted as blood clots in the brain).

Dracula became a success for critics as well as the audience when it was published by Archibald Constable & Co., Westminster, although it would take a long time before it achieved the monumental classical status it has today. Stoker had published theatre reviews, short stories and four novels between 1890 and ’95, but only a few of the stories had a horror motive. After the vampire orgy with the Transylvanian Count, he returned to the horror genre with

The Jewel of Seven Stars (1903) and the Gothic

The Man (1905). His last horror novels are reminiscent of

Dracula with a woman believed to be a vampire in

The Lady of the Shroud (1909), and with a vampire-like monster in

The Lair of the White Worm (1911), in which a seductive and murderous woman is actually a giant worm that lives hidden in the caves under a castle.

As early as January 1 to March 29, 1898, a Hungarian translation of

Dracula was published in the newspaper

Budapesti Hírlap, based directly upon the text of the 1897 novel. The following year,

Dracula was published as a serial in the American newspaper

Charlotte Daily Observer, starting on July 16, 1899, and completed on December 10, the same year. This text also matches the original novel and is available online in scanned form.

Prior to this, beginning on May 7, 1899, the daily paper

Inter Ocean in Chicago published the novel under the title

The Strange Story of Dracula. When Hans de Roos discovered this American serial publication earlier this year (2017), he overly enthusiastic went public and argued that it was the original of the Swedish

Mörkrets makter, a conclusion that he based solely on one single detail: that Lucy Westenra in a series of advertisements for the publication had the name misprinted as Lucy Western. However, this is a false track that he has abandoned, and copies of the serial published by him, as well as a description of the plot in an advertisement, show that

Inter Ocean simply published the text of

Dracula (1897) once again. De Roos is a natural force when it comes to ambitious excavations in databases and archives, but his enthusiasm sometimes gets the best of him.

These are the known instances of

Dracula in print until the time of the original publication of

Mörkrets makter in the newspaper

Dagen. It is not out of the question that

Mörkrets makter is a translation or adaptation of a similar version published in another country, but there is nothing to suggest this.

Mörkrets makter remains a unique version of

Dracula.

HARKER AND THE BLONDE FEMME FATALE

One of the most interesting differences between

Mörkrets makter and

Dracula is the presence of a blonde and blue-eyed vampire woman who is constantly seeking to seduce Harker in the castle of Draculitz and trying to lure him into corruption. In the text of 1897, there are three women, two dark and one blonde, who in one scene show erotic blood lust for Harker. Nevertheless, they play a rather insignificant role in the novel, unlike Harker's blonde man-eater in

Mörkrets makter. This is steaming eroticism:

Just then, two large, flaming summer lightning flashes, almost immediately following each other, illuminated everything with a bright electric light. In this glow she was suddenly in front of me –, quite close – – – dazzling – like a white flame, with the same tempting and enigmatic smile as when I first saw her eyes of blue fire, burning into my brain and causing my strength and will to melt like wax. I saw her thusly for a few seconds only, slender and yet voluptuous against the dim light in the room – then it was dark again [...]

Once again the quiet, fiery glow blazed, ghostly and otherworldly – it showed me her lovely face, close to my own, leaning over me, her eyes holding my eyes; the longing, voluptuous red lips were half-open, the jewel upon her white bare bosom, sparkling; I saw how she fell to her knees, next to the bench on which I was lying; in the next moment it was dark again, and in a dizzying half-conscious state, I felt as if I were sinking into an abyss [...] – – over my face I felt her breath, warm and intoxicating – – felt a pair of swollen lips pressed against my neck in a long, burning kiss that made my very essence tremble in the thrill of desire and anguish – and in an unbridled trance I enclosed the beautiful apparition in my arms – –

Compare this with the corresponding scene in

Dracula, where the blonde one of the women approaches Harker for the "vampire kiss." The scene is classic for its "sexiness", but appears lame in comparison.

DRACULA'S MYSTICAL GUEST

Bram Stoker's short story "Dracula's Guest" throws an interesting light on this blonde vampire woman. The story was published in 1914 in the collection

Dracula's Guest and Other Weird Stories edited by Bram's widow Florence. In the preface, she claimed that it was an unpublished part of

Dracula that had been deleted because the novel was too long. For a long time, the text puzzled

Dracula researchers, because it simply does not fit into the novel.

The story takes place outside of Munich during Walpurgis Night, on April 30, while

Dracula begins with Jonathan Harker arriving at Bistritz from Munich a few days later, May 3. "Dracula's Guest" was therefore assumed to be a deleted first chapter. But the events in this short story have nothing to do with the plot of the novel and the style is completely different from Jonathan Harker's other notes. Furthermore, the ending, with its allusion on Dracula, seems to be superimposed.

The Englishman in the story (Harker, but the name is not mentioned) goes out into the wilderness outside of Munich to visit a legendary deserted city. However, he is surprised by a violent snowstorm and finds shelter in a tomb. There lies a Countess Dolingen of Gratz, who committed suicide in 1801. Inside the bronze door, in the light of a flash, Harker sees a beautiful woman seemingly sleeping on a bier. The next lightning bolt eradicates the tomb at the same moment as the woman stands up. Harker is then found by some soldiers, semi-unconscious, at the ruin, where he was watched and kept warm by a great wolf which was licking his neck. As events evolve, it becomes obvious that it was Count Dracula who protected his future guest against the undead Countess by creating the rage of the elements, and in the form of the wolf kept him alive in the cold of the winter night.

Today, we know that "Dracula's Guest" really was a deleted part of a previous version of Dracula.; this mainly because of an unexpected find in the early 1980s in a barn in northwestern Pennsylvania, USA: Stoker's typescript for the vampire novel, very close to the final version of 1897. The typescript had belonged to Thomas Corwin Donaldson (1843-98), a Philadelphia lawyer, a close friend of Bram Stoker.

"Dracula's Guest" cannot be found in this typescript, either – but there are sentences and parts which overtly mention the fatal adventure during Walpurgis Night. These are fragments that were deleted before the final publication and apparently remained in the typescript by mistake. For example, Harker mentions this adventure in a discussion with Count Dracula, and here is a sentence in which Harker complains that his throat still aches after a gray wolf has licked it with its sharp tongue.

The episode is also suggested in Stoker's work notes for

Dracula: "Adventure snow storm and wolf." [EM p. 40.]

[1] In fact, the notes show that Stoker had provided

Dracula with an elaborated prehistory before Harker arrives in Bistritz, which was then rejected. In Munich, according to the notes, Harker stays at the Quatre Saisons, the same inn he stays at in "Dracula's Guest," but which is not mentioned in Dracula; and in the town he experiences strange events in a "dead house". During the trip from London, Harker is escorted by letters from Dracula, similar to the one at the end of "Dracula's Guest". [EM p. 10 & 40.]

Stoker's typescript reveals something further: The Countess in the tomb is identical to the blonde one of the three vampire women in Dracula's castle. In the scene where the women approach Harker and the blonde vampire tries to "kiss" him, the following passage can be found in the typescript, also deleted in the final version: "I was looking at the fair woman and it suddenly dawned on me that she was the woman – or her image – that I had seen in the tomb of Walpurgis Night..."

The description of this blonde vampire in

Dracula reads: "The other was fair, as fair as can be, with great wavy masses of golden hair and eyes like pale sapphires." – This is a brief description, but it is obvious that it conforms with the blonde vampire woman who besets Harker lasciviously in

Mörkrets makter. Some reviewers and commentators of

Makt myrkranna/

Powers of Darkness claim that she is drawn like a typical blonde, Scandinavian ideal woman, and that this is an example of an addition done by Ásmundsson on his own. However, the description is already to be found in

Dracula (1897).

Mörkrets makter also lacks an episode like "Dracula's Guest", but we get a rich background for the blonde vampire. She turns out to be a Countess "from the beginning of the century" in accordance with the dead countess in "Dracula's Guest"; she is not even mentioned as a Countess in

Dracula. How she died, however, is left to the reader's imagination – but it is very possible that she was driven to take her own life.

The language of "Dracula's Guest" differs significantly from the concentrated and unvarnished prose that Jonathan Harker uses in

Dracula (1897); on the other hand, it is in line with the language of

Mörkrets makter.

In addition to this it has to be mentioned that Stoker, in his work notes from 1892, really planned to use only one vampire woman and not three in Dracula's castle [EM p. 12] – a detail that was strangely overlooked in the English translation of

Makt myrkranna. In the very earliest notes, several women appear in Dracula's castle without their number being specified. For the final version, Stoker decided on three vampire women, the blonde still being given the most prominent role.

A LEAD FROM H.P. LOVECRAFT

It is quite clear from the circumstances surrounding "Dracula's Guest", that Stoker wrote earlier versions of

Dracula. But there is a more direct confirmation of this from an unexpected source, none other than the classic American horror writer Howard Phillips Lovecraft (1890-1937).

In a letter to Frank Belknap Long, October 7, 1923, he declared: "Mrs. Miniter saw 'Dracula' in manuscript about thirty years ago. It was incredibly slovenly. She considered the job of revision, but charged too much for Stoker." (

Selected Letters vol. 1.)

Mrs Miniter in the quote is Lovecraft's good friend, the writer and journalist Edith Dowe Miniter (1867-1934). They found common ground as friends in their mutual interest in New England's local history and their commitment to the United Amateur Press Association, an organization for amateur magazines and amateur journalism. They socialized from 1920 until her death, and during brief visits Lovecraft stayed at her home.

In a letter to Donald Wandrei, January 29, 1927, Lovecraft repeats almost the same information about Stoker's manuscript: "... it is curious to note that one of our circle of amateur journalists – an old lady named Mrs. Miniter – had a chance to revise the 'Dracula' MS. (which was a fiendish mess!) before its publication, but turned it down because Stoker refused to pay the price which the difficulty of the work impelled her to charge.” (

The Lovecraft Letters vol. 1.)

As well as in letters to R.H. Barlow Dec. 10, 1932: "I know an old lady who almost had the job of revising 'Dracula' back in the early 1890’s – she saw the original MS., & says it was a fearful mess. Finally someone else (Stoker thought her price for the work was too high) whipped it into such shape as it now possesses." (

O Fortunate Floridian.)

In another letter to Barlow in September 1933, Lovecaft added that Mrs. Miniter did not have any personal contact with Stoker: "She never was in

direct contact with Stoker, a representative of his having brought the MS. & later taken it away when no terms could be reached." (Same source.)

Finally, in a memoir of the recently deceased Mrs. Miniter, written in 1934 but published in 1938, Lovecraft provides additional information as well as a new part of the reason why Mrs. Miniter did not accept the assignment: "Notwithstanding her saturation with the spectral lore of the countryside, Mrs. Miniter did not care for stories of a macabre or supernatural cast; regarding them as hopelessly extravagant and unrepresentative of life. Perhaps that is one reason why, in the early Boston days, she had declined a chance to revise a manuscript of this sort which later met with much fame – the vampire novel Dracula, whose author was then touring America as manager for Sir Henry Irving." (According to the quotation in David J. Skals'

Something in the Blood.)

This has been claimed to show that Lovecraft gave conflicting information about the incident, but this claim is unfounded; Lovecraft is clear that he is speculating ("Perhaps that is one reason..."), and Miniter did not accept a lower sum for an assignment which did not interest her. That Stoker

also rejected her counteroffer does not implicate any contradiction, of course.

If Lovecraft's details are correct – it was, after all, 30 years later that he was told this by Edith Miniter – she was contacted about the job when Sir Henry Irving and his ensemble were on tour in the United States, backed by Bram Stoker. David J. Skal, in his Stoker biography, explains that the tour began in 1893 and came to Boston in January 1894, where Edith Miniter worked for the

Boston Home Journal, a weekly magazine for literature and art. Irving's productions were reviewed in the

Boston Home Journal – but in a remarkably scathing way; in fact, it was among the most negative reviews the Lyceum received during its tour of the US. Bram Stoker was the press contact during the tour, and Skal assumes that he contacted the editorial board for some diplomatic talk, as was his wont. With this, Skal suggests the possibility of a contact between Stoker and Miniter although it was not in the best circumstances; but it is conceivable that Stoker came to terms with at least Edith Miniter on the editorial staff. It is also conceivable that the contact between them was brought about completely independent of the

Boston Home Journal – after all, they moved in the artistic and literary circles of Boston at the same time.

MÖRKRETS MAKTER IN STOKER'S NOTES

In Eighteen-Bisang and Miller's

Bram Stoker's Notes for Dracula, the section "Limitations of the Notes," the editors explain that Stoker may well have written more notes for

Dracula than those present. The editors add: "Almost half the events in the novel are not mentioned in the Notes. Most of the interactions between human beings and vampires from chapters 16 to 27 [in

Dracula] are missing." They also make clear that it is "highly unlikely that Stoker moved directly from the Notes to the typescript. He probably bridged the gap between them with one or more lost drafts of the novel."

One of the striking correspondences between Stoker's work notes and

Mörkrets makter, but not with the

Dracula of 1897, has already been mentioned: The presence of a lone vampire woman who makes advances on Harker in the Count's castle. Here follows a number of other similarities that are missing in Stoker's finished novel:

In Stoker's notes, Lucy finds a "mysterious brooch" on the beach outside Whitby, probably meant to come from the wrecked ship that brought Dracula to England. This piece of jewelry then plays a mysterious role when Lucy is sleepwalking in Whitby's cemetery and gets attacked. [EM p. 18, 19 and 34.] In

Mörkrets makter, she falls under the influence of a similar mystical Piece jewelry when meeting the gypsies who have camped outside Whitby, and who are in collusion with Draculitz. The seductive blonde woman in Draculitz's castle wears the same kind of jewelry; and Harker receives a gift from the Count, a ring with a suggestively gleaming ruby Similar to the other pieces of jewelry. They have some kind of hypnotic impact on Harker and Lucy.

In the notes, the Count has a deaf-mute servant [EM p. 1 & 7], while the Count himself takes care of all the tasks of the household in

Dracula. The notes indicate that this woman is the Count's servant in England, but in

Mörkrets makter she is only present in Count Draculitz's castle. Another servant of Dracula is mentioned in Stoker's notes, a "silent man", possibly originally the coachman who brings Harker to the castle. In

Dracula, the Count himself plays the role of the coachman, as well as in

Mörkrets makter.

In the notes there is a detective Cotford. [EM p. 1 & 7.] This detective has a significant role in

mörkrets makter under the name Edward Tellet, subsequently assisted by another colleague named Barrington Jones.

In repeated notes Stoker mentions a blood-colored room: "Secret room – colored like blood"; "Count's house searched º blood red room"; "the blood room"; "Searching the Count's house – the blood red room"; "Secret search Count's house – blood red room". [EM p. 7, 8, 15, 27 & 34.] In

Mörkrets makter, this blood-colored room turns out to be the vampire Countess Ida de Gonobitz-Vàrkony's most intimate and dangerous chamber, where she lives on Draculitz's estate Carfax. Dr. Seward describes it thus:

I was in a bedroom, decorated with great luxury as well as illuminated by a hanging lamp with a blood red screen. Everything in the room was of the same color, in my opinion not very suitable for the calm, soothing atmosphere you would like to find in a bedroom – a strong flaming redness, which penetrated and filled the whole atmosphere. [...] Roofs and walls were covered with ruby red velvet; two of the large walls were almost entirely covered with immense mirrors, framed with red plush – the carpet had the same red color, and both windows and doors were completely covered in red draperies, while the bed itself was so dressed, draped and mattressed with silk and velvet in this deep, brilliant color, that it resembled a case for some expensive jewelry, more than an ordinary resting place.

Perhaps this room in deep red was originally meant to be Dracula's orgy chamber, but obviously it is better suited for a woman. In

Mörkrets makter, Draculitz has a similar room in another building where he seduces his victims, although arranged in a much more masculine fashion.

In Stoker's notes, Dr. Seward – the administrator of the insane asylum in the neighborhood of Carfax – is described as "a mad doctor". [EM p. 1 & 5.] In

Dracula, he has no problems with his own mental health, but in

Mörkrets makter it is a significant plot point that he understands he is on the verge of insanity, and at the end also becomes insane. His mind is suffering from the sorrow of Lucy's death and the fabulous experiences he is forced to undergo at Carfax.

Were Dr. Seward and Renfield originally one and the same person, whom Stoker then chose to divide into two characters? It would be logical if a mad doctor developed the theories of immortality and the flow of life-force in the development stages of the species, which are now thought out by the scientifically ignorant Renfield. However, the insane doctor and his patient are already mentioned on the very earliest pages of notes:

Mad Doctor – Loves Girl

Mad patient – theory of perpetual life

HOW MUCH BY STOKER?

All the details listed here are found in Stoker's notes from 1890 to 1892, according to their own dates and the order in which Eighteen-Bisang and Miller placed them. After 1892, the dating of the notes is very unclear, but the notions approach the final version of Dracula. The draft which was the basis of

Mörkrets makter seems to have been written at this stage or soon afterwards.

However,

Mörkrets makter cannot possibly be a straight translation of this early draft. Jonathan Harker, Mina Murray, Lucy Westenra and Dracula are named with their final names already in these early notes 1890-92, but have been changed to Thomas Harker, Vilma Murray, Lucy Western and Count Draculitz respectively in the Swedish adaptation. In

Mörkrets makter there are allusions to world events that occurred after

Dracula's original edition in 1897, with examples such as the "Orlean conspiracy" 1898-99. In the section with the human sacrifices under Dracula's castle, the flame-lit scene is compared with the flickering pictures of the cinematograph. The cinematograph (the first film projector) was not patented until 1895 and began to be used commercially only in 1896.

The big question is how much has been adapted or elaborated by "A–e". Stoker's early draft must have contained the pre-history before Harker arrives at Bistritz. The fact that it was deleted suggests that the editor was inspired by

Dracula 1897 during the work. The whole subplot about Draculitz's political conspiracy of a fascist nature can be a Swedish addition based on the Social Darwinistic hints already in Dracula,

[2] which would explain the hybrid-like impression given by the vampire theme in combination with political thriller and satire. The theme of

fin de siècle – the pessimism and decadence at the end of the 19th century – in the last quarter of the novel seems to have been added to make the novel contemporary; this closing part was published in the newspaper

Dagen from December 1899 until early February 1900.

However, there is a strange hint to immortality and high politics also in Stoker's early notes: "Immortaliable – Gladstone". [EM p. 6.] William Gladstone was the Prime Minister of the UK and a good friend of with Sir Henry Irving. And after all, the style of the language is remarkably consistent throughout the novel. The text is also in no small amount interspersed with translation mistakes in the form of Anglicisms.

At this stage, it is simply not possible to know how much of the text reflects Stoker's original draft, and how much is deleted, added and reworked by "A–e".

BRAM STOKER AND SWEDEN

Dracula had already attracted attention abroad. Why did not the editorial office behind

Dagen and

Aftonbladets Halfvecko-Upplaga just translate the already released novel straight off? It would both be cheaper – Sweden had not yet entered the Bern Convention at this time, wherefore pirated translations of foreign writers were par for the course – and, more importantly, significantly cheaper than paying the signature A–e for a "Swedish adaptation" twice as long as the original novel. At least A–e was paid for this gigantic work, one can safely assume. This was not a simple pirate edition among others.

The editorial staff of

Dagen and

Aftonbladets Halfvecko-Upplaga certainly expected that they, with Stoker's draft as a basis, had a guaranteed literary success, a future alternative classic to

Dracula 1897.

However, the hope of success was frustrated. Only the Icelandic translation of

Aftonbladet's shortened text was realized, and the two Swedish versions were never printed in any separate book editions.

[3] The novel was published only one more time 16 years later in the cheap weekly magazine

Tip-Top – and then fell into oblivion. The circumstance that the serial in

Aftonbladets Halfvecko-Upplaga was shortened radically after the initial part had been printed, can also be interpreted as a result of the success that never happened; they wanted to leave room for new serials as soon as possible, which hopefully would appeal better to the audience.

How did Bram Stoker's draft end up in Sweden? Here we come to the author and playwright Anne Charlotte Leffler (1849-92) and her brother, a mathematician and man of art and culture, Gösta (Gustaf) Mittag-Leffler (1846-1927).

Anne Charlotte Leffler, today rather forgotten, addressed mainly women's liberation in her drama. She was a highly successful, much-disputed and controversial writer even internationally during her lifetime; she is said to have attracted more attention in England than Henrik Ibsen. Her brother Gösta Mittag-Leffler was, for his part, an internationally renowned professor of mathematics, member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and honorary member of the Royal Society in England. Yet, he also held a strong interest in culture and literature and was diligently involved in the literary circles of Stockholm, where he acted as a debater in cultural and political matters. In 1914, he was prosecuted and convicted for defamation of the Prime Minister Karl Staaf; however, the verdict was thrown out by the Supreme Court because of formal inaccuracies in the prosecution.

In the manuscript collection at the National Library of Sweden, letters and messages are kept, which show that Anne Charlotte Leffler and Gösta Mittag-Leffler were good friends with Bram Stoker's siblings, and thus probably with Bram himself. A letter to Anne Charlote Leffler from Bram Stoker's brother George Stoker (1854-1920), dated 1887, is preserved, as well as an undated business card from him to Gösta Mittag-Leffler. In the National Library there are also 7 letters to Gösta Mittag from Bram's sister Margaret Dalrymple Stoker (1853-1928), written from around 1874 until 1883. There are also three undated letters of 1875 to Gösta from a Mathilde Stoker. It is unclear whether this is Bram Stoker's mother Charlotte Mathilda Blake Stoker (1818-1901) or his sister, the artist Charlotte Matilda Stoker Petitjean (1846-1920). The correspondence is commonplace and does not contain anything of particular interest for a literary scholar; however, it shows that the contact between the Leffler and Stoker siblings was extensive and familiar.

But there is more. On the whole, Anne Charlotte Leffler had extensive contacts also with friends of Bram Stoker; she simply moved in the same circles. At the National Library there is a letter to her, undated but written in 1884, from Francisca Elgee Wilde, more famous as Jane Wilde (1821-96) – Oscar Wilde's colorful mother. In Dublin she ran a literary salon where young Bram Stoker was a frequent visitor. He started hanging out with the family and became a dear friend of her son’s. David J. Skal describes their friendship in detail in

Something in the Blood. Bram Stoker's wife Florence also had a relationship with Oscar Wilde before she abandoned him for Bram.

In one of Anne Charlotte Leffler's letters to Adam Hauch, quoted in her letter and diary collection

En självbiografi (1922), she describes her encounter with Lady Wilde during a stay in London in 1884:

I have made acquaintances in a lot of literary circles. The other day I received an invitation to a Lady Wilde, a well-known literary lady, who is just publishing a book about Scandinavia, in which she mentions me as one of the leading authors at home, and she necessarily wanted to meet me, when she was told that I was here. It was the most precious parties I ever had. Her son, Oscar Wilde, famous poet and leader of the so-called Aesthetic movement here, usually wears breeches and a Spanish coat, she never shows herself in daylight, wherefore her room was darkened in the middle of the day and only illuminated by an artificial red light – dressed in a light, deep decollated silk dress (on a morning reception) very painted, the furniture the most motley bric-a-brac, remnants of their former glory, but broken, which was not meant to be seen in the dusk – – –.

Lady Wilde as a vampire? The Irish writer lived at this time in misery in London, after her husband died bankrupt a few years earlier.

Was Oscar Wilde himself present at the gathering? It is possible to read her letter in that way. In Leffler's diary of May 9 that same year, she and Oscar Wilde even visited a "hermetic society" in London: "Mystical drawing-room meeting. Hermetic, theosophical society in evening dress. Doctor Mrs. Kingsford loveable, beautiful, intelligent, very self-aware, yellow-red hair, tall and slim, pale face. Oscar Wilde with 'nasty looks' on limping, pockmarked miss Lord. Two hermetic celebrities speaking."

Monica Lauritzen's biography

Sanningens vägar: Anne Charlotte Lefflers liv och dikt (2012) recounts that Leffler was a frequent theater-goer during the same period in London, most impressed by Sir Henry Irving's version of Shakespeare's

Much Ado About Nothing, which she must have seen at the Lyceum Theatre. Unfortunately, Lauritzen does not provide many concrete details about this event. Was Leffler introduced to the great actor after the performance? At least it would be bad etiquette if she did not exchange words at the Lyceum with Bram Stoker, whose brothers and sisters she had such good contact with. Generally we have to assume that Leffler socialized with the Stoker siblings during her time in London, although it is not evident in the letters and diary notes known to date.

Exactly how it happened when Bram Stoker's draft of

Dracula came to

Aftonbladet's editorial office in Stockholm, we do not know, but it is a very strong working hypothesis that Anne Charlotte Leffler and Gösta Mittag-Leffler have something to do with it. Much more research is needed than has been possible to do so far.

Anne Charlotte died in October 1892 of appendicitis, but Gösta continued to be active in the literary circles of Stockholm until his death in 1927.

THE SIGNATURE A–E

Who was the signature "A–e" who undertook to revise Stoker's draft into a readable novel? Briefly, it is hidden in obscurity and something that requires more research as well. The signature was a one-off event in

Dagen and

Aftonbladets Halfvecko-Upplaga. The dash that connects the "A" with the "e" seems to suggest that it is a masked name, such as Alice or Anne. But of course it is more than unlikely that Anne Charlotte Leffler was the editor of

Mörkrets makter, not least because she died as early as 1892.

It can also be a shortened nickname. A writer in provincial newspapers, Algot Agelborg, sometimes used the signature A–e for his nickname "Agge", but born in 1894, he was only five years old when the serial was published. Birger Landén (1846-1927), a minor debater on religious issues, sometimes used the signature A..e. Apparently, he produced no fiction or translations, and nothing indicates that he had a connection to

Dagen or

Aftonbladet.

As for the signature A.E. and variants on it, there is no lack of candidates; for example, the authors Albert Andersson-Edenberg (1834-1913), Albert Engström (1869-1940) and Daniel Bergman (1869-1932). All of these had connections to

Aftonbladet. Albert Engström even wrote a Gothic horror novel in the form of

Ränningehus (1920); but much is needed to believe that this legendary humorist, cartoonist and writer was behind the signature A–e.

Faithful to his habit, Hans Corneel de Roos has speculated lively about who A–e may have been. According to his first proposal in an article in March 2017, A–e was an abbreviation for "

Aftonbladet's editor" (sic!), in other words,

Aftonbladets and

Dagens editor-in-chief Harald Sohlman. This reasoning can be dismissed because of its own absurdity (the Swedish word for editor is

redaktör). His next proposal, in May 2017, he brought forward as indubitable: that A–e was

Aftonbladet's co-worker Albert Andersson-Edenberg, based on the fact that he sometimes signed his articles and translations with A.E. and A.-E. – and had written an article in

Svenska Familj-Journalen about antique iron-clad doors. In Dracula's castle in

Mörkrets makter there are also ancient iron-clad doors! But such a detail is exactly what you can expect in an ancient castle. De Roos claimed that he found many more similarities between

Mörkrets makter and articles written by Andersson-Edenberg, but did not give an account of them. If any of this evidence was stronger than the case of the iron-clad door, he would probably have mentioned it instead.

It is still too early to point out someone as the identity behind A–e. All this, including information about the connection between the Leffler and Stoker siblings, requires careful and thoughtful research before any truths are established.

You will have to wait and see. Follow this story and how it develops here at

Weird Webzine.

* * *

Rickard Berghorn (born 1972) is the editor of

Weird Webzine and the Swedish publishing house Aleph Bokförlag. He has written short stories published in, for example, Sam J. Lundwall's magazine

Jules Verne-Magasinet and radio plays for Swedish Radio broadcasted nationally. Together with Annika Johansson, he wrote the first Swedish presentation of the history of the horror genre,

Mörkrets mästare ("Masters of Darkness", BTJ Förlag 2006). He was Nordic Guest of Honor at the fantasy and science fiction congress

FinnCon 2006.

NOTES

[1] EM stands for Eighteen-Bisang & Miller, the two scholars who edited Stoker's work notes; the page numbers represent the order in which EM placed them. See Bram Stoker's Notes for Dracula (2008). The notes had been studied by a handful of researchers since the 1970s but were published by Eighteen-Bisang & Miller in 2008.

[2] Mathias F. Clasen analyzes this in depth in his dissertation Darwin and Dracula: Evolutionary Literary Study and Supernatural Horror Fiction (Department of English, Aarhus University 2007).

[3] However, it can be mentioned that the serial was published in book page format in Dagen and Aftonbladet's Halfvecko-Upplaga, in a way that made it possible to cut out the sheets and hand them over to a book binder. This was a common way of publishing serials in Sweden in the 19th century.

REFERENCES

Many thanks to Martin Andersson and Jan Reimer for help with references. The abovementioned letters etc. from the Stoker siblings and Jane Wilde can be found in the manuscript department of the National Library of Sweden, and they mainly belong to the Gösta Mittag-Leffler Archive. Most of them have not yet been registered in the National Library's databases but were obtained upon request in February 2017. Thanks also to Karin Sterky at the National Library for help with this.

• Bygdén, Leonard: Svenskt anonym- och pseudonym-lexikon vol. I (Uppsala: Akademiska Boktryckeriet 1898-1905). On the net <runeberg.org/sveanopse>. Access date 2017-09-28.

• De Roos, Hans Corneel: Next Stop Chicago! Earliest U.S. serialisation known so far discovered. Was it the source for Mörkrets Makter? On the net <vamped.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/HansDeRoos_For-Vamped-Org_v12.pdf>. Access date 2017-09-28.

• De Roos, Hans Corneel: The True Source of Makt Myrkranna? (Children of the Night Dracula Congress. Official Bulletin of the Brașov Congress Initiative. No 1, March 2017). On the net <dracongress.jimdo.com/conference-bulletin>. Access date 2017-09-28.

• Eighteen-Bisang, Robert & Miller, Elizabeth: Bram Stoker's Notes for Dracula: A Facsimile Edition (London & Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. 2008. ISBN 9780786 434107).

• "Icelandic version of Dracula, Makt myrkranna, turns out to be Swedish in origin." Article in the Iceland Monitor 6/3 2017. On the net <icelandmonitor.mbl.is/news/culture_and_living/2017/03/06/icelandic_version_of_dracula_makt_myrkranna_turns_o>. Access date 2017-09-28.

• Lauritzen, Monica: Sanningens vägar: Anne Charlotte Lefflers liv och verk (Stockholm: Bonniers 2012. ISBN 9789100130275).

• Leffler, Anne Charlotte: En självbiografi: Grundad på dagböcker och brev (ed. Jane Gernandt-Claine & Ingeborg Essén. Stockholm: Bonniers 1922).

• Lovecraft, Howard Phillips: Selected Letters I: 1911-1924 (ed. August Derleth & Donald Wandrei. Sauk City, WI: Arkham House 1965).

• Lovecraft, Howard Phillips: The Lovecraft Letters: Mysteries of Time & Spirit: Letters of H.P. Lovecraft & Donald Wandrei vol. 1 (ed. S.T. Joshi & David E. Schultz. Night Shade Books 2005. ISBN 1892389509).

• Lovecraft, Howard Phillips: O Fortunate Floridian: H.P. Lovecraft's Letters to R.H. Barlow (ed. S.T. Joshi & David E. Schultz. Tampa, FL: University of Tampa Press 2007. ISBN 9781597320344).

• "Orleans, Louis Philippe Robert, Duke of." Article in Encyclopædia Britannica vol. 20, 1911. On the net <en.wikisource.org/wiki/1911_Encyclop%C3%A6dia_Britannica/Orleans,_Louis_Philippe_Robert,_Duke_of>. Access date 2017-09-28.

• "Pretenders Watching the French Throne." Article in the Chicago Tribune 1898-11-13.

• "Pseudonym- och signaturregister" in Lundstedt, Bernhard: Sveriges periodiska litteratur (Stockholm: Idun 1895-1902). On the net <www.kb.se/Sverigesperiodiskalitteratur>. Access date 2017-09-28.

• Publicistklubbens porträttmatrikel (Stockholm: Publicistklubbens förlag 1936). On the net <runeberg.org/pk/1936/0005.html>. Access date 2017-09-28.

• Skal, David J: Something in the Blood: The Untold Story of Bram Stoker, the Man Who Wrote Dracula (London & New York: Liveright/W.W. Norton 2016. ISBN 9781631490118).

• Stoker, Bram: Dracula (New York: Grosset & Dunlap 1897). On the net <www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/345>. Access date 2017-09-28.

• Stoker, Bram & Ásmundsson, Valdimar: Powers of Darkness: The Lost Version of Dracula (London & New York: Overlook Duckworth 2017. ISBN 9781468313376).

• Svenskt biografiskt lexikon. On the net <www.riksarkivet.se/sbl>. Access date 2017-09-28.