When Howard Hawks (1896-1977) planned to make a screen version of Raymond Chandler's

The Big Sleep in 1946, he happened to read "No Good from a Corpse" by Leigh Brackett (1915-78). Hawks was not overly impressed by the story, but he most certainly appreciated the dialogues. It is understandable. The story is perhaps not that good, but the way it is written. "Wow!" he said, "get me that Brackett guy" or words to that effect.

To his surprise a lanky young woman turned up at his office. And who can blame him? Leigh is an ambiguous first name, mostly interpreted as a male name. And how could he possibly imagine in those days that a woman wrote the most hardboiled and hard-hitting punch cues in Hollywood?

Hawks straightaway overcame his surprise, hired her and in the long run Leigh Brackett became his favorite scriptwriter. She was professional and reliable. Over the years, he summoned her over and over again. And lo, in this the 21st century, her old crime stories and space operas are brought to light and praised again.

A WRITER OF MANY TALENTS

In retrospect, Leigh Brackett turns out to be a somewhat different bird in the world of writers. She moved freely and without any apparent difficulties between differing genres like mysteries, westerns, fantasy, science fiction. Certainly, other writers have done the same, but on top of that, she moved equally unhindered between different media: novels, short stories, films, TV, radio. Just imagine how many combinations you can get out of that.

In addition to her brilliant handling of dialogues, she had an excellent faculty for visualizing and an impressive ability to characterize; and at the end many of her stories are replete with over- and undertones of a rare existential quality.

When James Sallis reviewed

Martian Quest: the Early Brackett (Haffner Press, 2002) in

Fantasy & Science Fiction, he stated that as "with many true originals, much of Brackett's work, for all its seeming diversity – hardboiled, standard mystery, Westerns, high fantasy, science fiction – falls in a straight line."

Sallis points out that her first published short story, "Martian Quest," is "a transliteration of the standard Western plot: stranger with mysterious past rides in from off-planet to a farming community in the reclaimed Martian desert, meets a fine woman, encounters distrust and rejection, solves the community's problems and saves all."

But I do not think of science fiction when I read her crime stories. I do not think of fantasy when I read her western stuff. I do not think of mysteries when I read her space operas and – in spite of Sallis' accurate observation – I do not even think of Westerns when reading "Martian Quest."

There may be similar plots, similar frames of minds and atmospheres in her writing. Even though she was not a stranger to crossover genres and subcategories, at the end there are sharp dividing lines between many of the different genre stories she tried her hand and mind at. The cruel but outstanding

noir story "Red-Headed Poison" (1943) has for example very little in common with the science fiction story "The Jewel of Bas" (1944) – the latter in itself a gem.

Furthermore, her prose is captivating, and I am not really tempted to analyze whether it is this or that while reading. When she was commissioned to turn some other writer's story into a screenplay, instantly she was able to adjust her own attitudes to the other writer's (or Howard Hawk's) mind, but she always added that Brackett touch to it. She knew what she was doing and possessed an immediate ability to visualize scenes and create matchless dialogues, cues and one-liners.

LEIGH, THE TOMBOY

Leigh Brackett grew up in Santa Monica, a tomboy with a weakness for boyish plays and games. She swam, devoted herself to amateur theatre, and in the summers she was a swimming instructor. Ray Bradbury once recounted how he watched Leigh Brackett playing volleyball with the men during WWII at Muscle Beach in Santa Monica.

"I've always been bent on masculine things", she told the writer of this essay in 1975. Despite titles like "The Dragon-Queen of Venus" (1941), "Lorelei of the Red Mist" (1946), "Enchantress of Venus" (1949) and "The Woman from Altair" (1951), her heroes are men. Her women are at most catalysts – sometimes, but certainly not always – of a tempting, grim and dangerous kind.

In this connection I would like to cite the Swedish science fiction and mystery specialist John-Henri Holmberg. Swedish film critics have had a tendency to give Hawks credit for portraying strong women in his movies. Holmberg scolded the reviewers for not taking into consideration that it actually was a woman who had written the scripts for those movies.

Brackett's first and last love was science fiction – or rather the combination of the science fictional subgenre space opera and the fantasy subgenre called sword & sorcery, a combination described as 'scientific romance' by science fiction historian Sam Moskowitz. "Planetary romance" is perhaps a more fitting label.

She was inspired at an early age by Edgar Rice Burroughs (ERB). Not exactly the ERB of

Tarzan of the Apes, but the ERB whose

Under the Moons of Mars (1912) became a landmark novel of the genre. Besides books and film, the golden years of radio affected her. The American radio waves in the 1930's and 1940's vibrated with exciting dramas, entertaining mysteries and romantic soap operas. Those were the days of

The Shadow and

Mercury Theatre of the Air, with Orson Welles.

HER CAREER BEGINS

She had a grandfather who supported her efforts to sell her first stories. She turned to an "agency-cum-writing-course," where Henry Kuttner discerned her talents. Through him, she got into contact with other writers in Los Angeles. The year was 1939. She was 24 years old then and got her first short story, "Martian Quest," published in

Astounding Science Fiction in February 1940.

Between 1940 and 1943, she wrote a series of short stories for magazines like

Planet Stories, Startling Stories, and

Super Science Fiction. They were simple but promising stories foreshadowing things to come. And soon she penned perhaps the best of her existential short stories, "The Veil of Astellar," a significant and different contribution to the space opera genre. It was published in

Thrilling Wonder Stories in the spring issue of 1944. It is a unique story, one of the most remarkable, tragic and well-written existential hero tales worth considering.

At the same time as she churned out a stream of planetary romances, she also had begun penning a series of extraordinary hardboiled criminal stories for the mystery pulps. In 1944 she got her first full-length novel published. It was not a planetary sword & sorcery opera but the crime story "No Good From a Corpse" (reprinted together with her collected short criminal stories by Dennis McMillan, 1999).

The dialogues of her short science fiction stories were not bad, but when it came to writing tough cues in the tradition of Hammett and Chandler, two hardboilers she admired, Brackett was ahead of most other writers.

Leigh Brackett's period as a writer of short hardboiled detective stories was in itself as short as the stories. As far as I know, eight short stories between 1943 and 1945 for down-market pulps like

New Detective and

Thrilling Detective with a temporary relapse into the genre for

Argosy in the late 1950's.

Unlike her planetary romances, her hardboiled stories were in every respect cast in the Chandler mould. She did not really add anything to the genre as such, but as Bill Pronzini puts it, referring to "No Good From a Corpse," she was so "Chandleresque in style and approach it might have been written by Chandler himself." Pronzini even called her "one of the top hardboiled writers of all time." And it is true that she almost outdid Chandler on his own half of the ground.

It was in 1946 that Howard Hawks read "No Good From a Corpse" and entered the action, thus diverting her from short stories and novels to screenwriting. Actually,

The Big Sleep was not Leigh Brackett's first job as a screenwriter in Hollywood. Forgotten are

The Vampire's Ghost and

Crime Doctor's Manhunt, potboilers of 1945.

With Howard Hawks' intervention in her life, her career as a screenwriter made a quantum leap. But over the years she seems to have been underpaid as compared with Jules Furthman and other rather lazy but well established screenwriters.

HER FRIEND RAY BRADBURY

At that point when Hawks summoned her to his office, she had prepared half of the 20,000-worder "Lorelei of the Red Mist" for

Planet Stories. She had written the line "Then it was gone, and the immediate menace of the foreground took all of Starke's attention." At the same time that she wanted to accept Hawk's offer, the assigned story had to be finished. She had to make some kind of decision.

The dilemma was solved. Ray Bradbury was five years younger than Leigh Brackett. She was a kind of mentor and a sounding board for this aspiring writer. She turned to Bradbury and asked him to complete the story. He accepted the challenge.

Where Brackett had stopped writing the story, Bradbury jumped into

medias res and continued with the following sentence, "He saw the flock, herded by more of the golden hounds." Then he completed the story in ten days and "Lorelei of the Red Mist" was published that same year. The rest is, if not exactly history, at least science fiction history, for this Brackett-Bradbury collaboration is famous among knowledgeable science fiction fans.

However, Leigh Brackett now turned from one collaborator to another one, from Ray Bradbury to William Faulkner, who still had a few years to go before being awarded the Nobel Prize for literature. Faulkner now worked for Howard Hawks. "Faulkner came in to me with Chandler's

The Big Sleep. He tore the book in two pieces and gave one of them to me. 'I do this part and you do this', Faulkner said. And that was just about all I saw of him."

A HOME WITH EDMOND HAMILTON

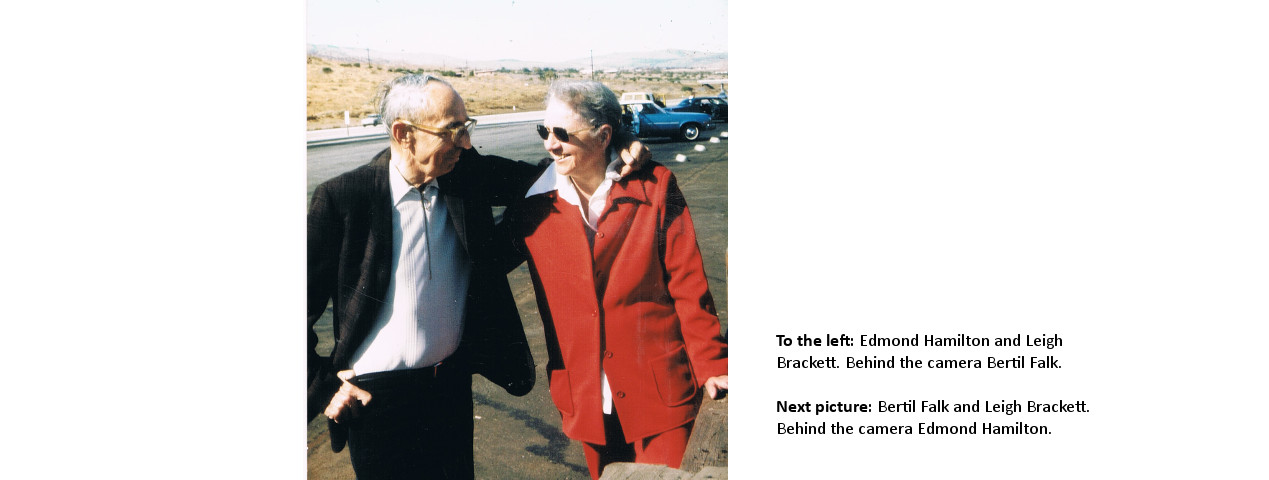

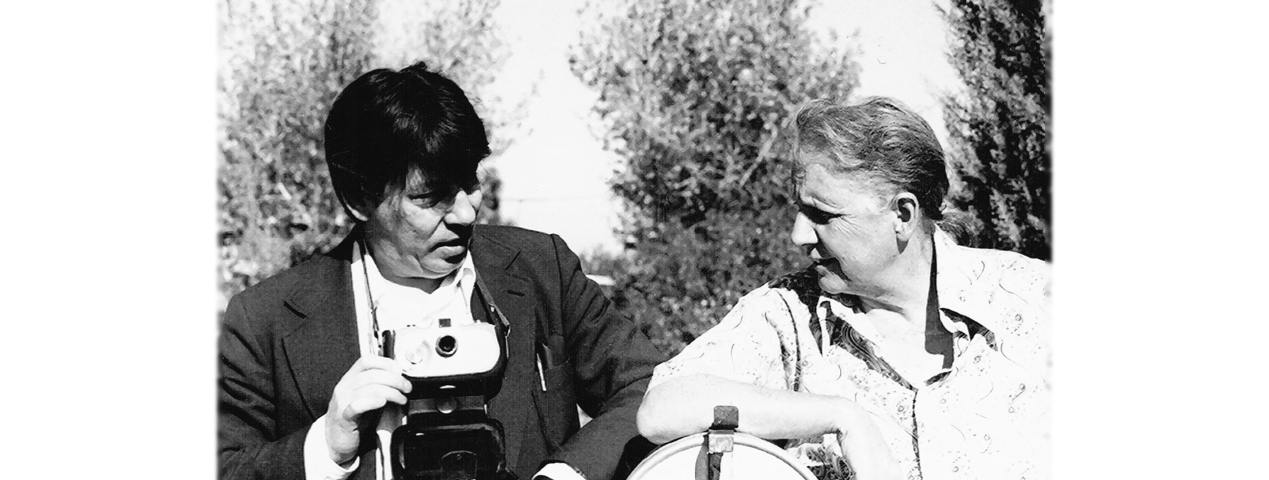

That is what Leigh Brackett told me when I visited her husband Edmond Hamilton (1904-77), the creator of my boyhood hero Captain Future, in their winter home in Lancaster, California in 1975. She had married Hamilton, a space opera king of the pulp field, on January 1, 1947 with Ray Bradbury as best man. I had begun reading Edmond Hamilton's Captain Future stories translated into Swedish at the age of nine in 1942.

They picked up the journalist and Hamilton-fan from Sweden at the Greyhound terminal in downtown Los Angeles and took me in their car to their home. On the way to Lancaster, Leigh Brackett, who loved driving fast cars, stopped and they let me take a look down at the San Fernando fault zone.

Had it not been for the fiery red color of coat and trousers, Leigh's clothes could have been inspired by John T. Molloy's

Women's Dress for Success. Now, outlined against the sky, she was like a blood-red splash of color ready to replace the sun any minute. She did not do anything of the kind. Instead, after contemplating the intrinsic power of the geography below us, she returned with us to the car.

I had come to interview Edmond Hamilton and slept one night in Leigh Brackett's study, a small house besides the main building. After interviewing Ed, I also took the opportunity to interview Leigh Brackett, then a writer I had not read, except for a short Mercury story published in Swedish in 1941, though I had seen

The Big Sleep. So I asked her about that period of her life.

"I was young and curious and was at the studio all the time during the shooting. One day Humphrey Bogart came over to me with a manuscript and asked if I had written the cues. I said no and he said, 'They cannot be said'. You see, William Faulkner wrote wonderful Faulkner dialogues, but they were not written to be uttered. Faulkner went down in history as the screenwriter whose every single line was rewritten in Hollywood."

Later on, I got to know that Howard Hawks himself sat by ringside during the shooting and rewrote Faulkner's lines more or less like the way a student's essay is critiqued. Raymond Chandler visited the studio and was very pleased with the job Leigh Brackett had done. But a craft-union strike hit the movie business in the summer of 1946. No more script-writing jobs were available. Leigh Brackett went back to writing her space opera stories. And that is the way it was to be. She took on many assignments of different kinds over the years, but when done, she always returned to her space opera adventures.

Edmond Hamilton admired the ease with which his wife moved, in his own words: "From one kind of fiction to a completely different kind. In eighteen months, in 1956-57, she wrote not only

The Long Tomorrow but also two novels of crime and suspense,

The Tiger Among Us, which became an Alan Ladd movie, and

An Eye for an Eye, which formed the pilot for the 'Markham' series on television. At the end of that period, she returned to Hollywood and to her old producer Howard Hawks, to write

Rio Bravo, the first of a series of John Wayne action epics she wrote."

The other scripts she wrote for Hawks and Wayne were

Hatari! (1962),

El Dorado (1967) and

Rio Lobo (1970). When she wrote

El Dorado, Hawks and Wayne wanted her to borrow a scene used in Rio Bravo. Leigh Brackett was against repeating the scene. John Wayne shared Hawks' opinion and argued that since it worked then, it would do so again. Edmond Hamilton remembered that his wife knew when she was outgunned. She wrote the scene.

HOW TO WRITE A STORY

There are many ways to write a story. Marcel Proust stayed in bed year after year and wrote and wrote and never quite finished his

Remembrance of Things Past. It is said that Nobel laureate Pär Lagerkvist, who wrote

Barabbas, could spend a week rewriting and polishing one single sentence. In order to make a living, F. Scott Fitzgerald "tore off" short stories for the slick market, but at the same time he took his time when he wrote

The Great Gatsby and other novels. He was even more careful when he plotted and structured

The Last Tycoon and spent the last years of his life on the draft that was unfinished when he died in 1940.

Similarly, Edmond Hamilton plotted and structured his stories before he wrote them. Hamilton met Leigh Brackett in 1940 and he was least to say impressed by stories like "The Jewel of Bas" and "The Veil of Astellar." But while Hamilton knew what he was going to write when he sat down by his typewriter, Brackett had no idea whatsoever of the direction her stories would take when she sat down at hers.

In his introduction to

The Best of Leigh Brackett (Ballantine, 1977) Hamilton wrote: "We found, when we first began working together, that we had quite different ways of doing a story. I was used to writing a synopsis of the plot first, and then working from that. To my astonishment, when Leigh was working on a story and I asked her, 'Where is your plot?' she answered 'There isn't any... I just start writing the first page and let it grow.' I exclaimed, 'That is a devil of a way to write a story!' But for her, it seemed to work fine."

Over the years the two affected each other's writing. Leigh Brackett learned plotting from her husband. Even though he plotted his stories before he wrote them, he had nevertheless been a hack writer all the way from "The Monster-God of Mamurth," published in

Weird Tales, August 1926. Under the influence of his wife, he stopped using his typewriter as a machine gun. He no longer wrote in a hurry and took an interest in carefully forming his sentences.

When

Startling Stories asked Hamilton, in 1950, to revive Captain Future for a series of short stories, he was busy working on other assignments. He wrote the first story "The Return of Captain Future." Then he wrote the synopses for the other stories. But when I visited them, I was told that it was actually Leigh Brackett who wrote them under his guidance using the "pen name" Edmond Hamilton.

In 1964 it was the other way around, when Hamilton expanded Leigh's short story "Queen of the Martian Catacombs" into "The Secret of Sinharat" and "Black Amazon of Mars" into "The People of the Talisman." Both stories were originally penned in the 1940's.

This matrimonial co-operation went even deeper than that. With "Stark and the Star Kings" they pooled their resources and brought together their heroes Eric John Stark and John Gordon. The story was not published until 2005 in the collection

Stark and the Star Kings (Haffner Press Royal Oak, Michigan).

PULP QUALITY?

In his introduction to

Martian Quest: The Early Brackett (Haffner Press 2002), Michael Moorcock points out that her stories appeared "in what I believe were the superior pulps, containing more vivid and often more lasting fiction than the admired

Astounding and

F&SF; which were considered more prestigious in their day. I preferred the pictures in

Fantastic, particularly when they were by Finlay. With Weird Tales and Campbell's excellent

Unknown, for me

Planet Stories, Thrilling Wonder Stories and

Startling Stories all contained more idiosyncratic writing, more stylish innovation, than an entire run of the more respectable SF magazines."

Michael Moorcock's remark is underlined by the fact that Ray Bradbury's novel

The Martian Chronicles was originally published in the form of short stories in the down-market pulp magazine

Planet Stories. Bradbury-specialist Jerry Weist, who wrote

Bradbury: an Illustrated Life (William Morrow, 2002) thinks that

The Martian Chronicles is THE science fiction book that will survive when other science fiction stories are forgotten.

And I would like to add that it seems to me that

The Martian Chronicles, together with the ultimate space opera novel, Alfred Bester's ingenious paraphrase of Monte Cristo,

The Stars My Destination (

Tiger! Tiger!) is one of two science fiction masterpieces of the English language literature of the past century. Both are unique and incomparable, without parallel.

Anyway, when Leigh Brackett got an opportunity to defend the "lousy" pulp magazine and the appalling space opera in her introduction to

The Best of Planet Stories #1 (Ballantine Books, 1975), she unburdened her heart in a way that showed commitment to the hilt:

"

Planet, unashamedly, published 'space opera'. Space opera, as every reader doubtless knows, is a pejorative term often applied to a story that has an element of adventure. Over the decades, brilliant and talented new writers appear, receiving great acclaim, and each and every one of them can be expected to write at least one article stating flatly that the day of space opera is over and done, thank goodness, and that henceforward these crude tales of interplanetary nonsense will be replaced by whatever type of story that writer happens to favor – closet dramas, psychological dramas, sex dramas, etc., but by God

important dramas, containing nothing but Big Thinks. Ten years later, the writer in question may or may not still be around, but the space opera can be found right where it always was, sturdily driving its dark trade in heroes."

And she goes on, giving a reason for her strong opinion, showing that it has not appeared out of thin air:

"The tale of adventure – of great courage and daring, of battle against the forces of darkness and the unknown – has been with the human race since it first learned to talk. It began as a part of the primitive survival technique, interwoven with magic and ritual, to explain and propitiate the vast forces of nature with which man could not cope in any other fashion. The tales grew into religions. They became myth and legend. They became the Mabinogion and the Ulster Cycle and the Voluspa. They became Arthur and Robin Hood, and Tarzan of the Apes. The so-called space opera is the folk-tale, the hero-tale, of our particular niche in history."

Science fiction at its very best is the genre that by definition can be said to be at least next to existential by nature. Here the imagination of life and death and time and space and past and future are intertwined in a way you will not generally find within mainstream or mystery or any other literary genre for that matter.

And if anything, Leigh Brackett is an existential writer. An exquisite and beautiful tale like "The Veil of Astellar," perhaps the most sparkling ruby in her diadem of precious gems, creates a numbing sense of powerlessness, which seems to be the unfathomable tragedy of human fate. It is a story where the spirit of painful human self-sacrifice in a most strange context is explored. The "hero" of the story knows that he has gone beyond humanity and can't turn back:

Maybe prayer doesn't matter. Maybe there's nothing beyond death but oblivion. I hope so! If I could only stop being, stop thinking, stop remembering. I hope to all the gods of the universe that death is the end. But I don't know, and I'm afraid. Afraid. Judas-Judas-Judas! I betrayed two worlds, and there couldn't be a hell deeper than the one I live in now. And still I am afraid. Why? Why should I care what happens to me?

Not exactly the kind of stuff you expect from a pulp magazine. Brackett wrote that the stories in

Planet Stories were "written to be entertaining, to be exciting, to impart to the reader some of the pleasure we had in writing them." This abruptly reminds me of what Julian Symons wrote about stories published in the British

Strand Magazine: "Most of them were written with no more serious purpose than to occupy a reader's attention for an hour; yet the best do more than that, leaving echoes in the mind."

"The Veil of Astellar" leaves echoes in my mind.

LEIGH BRACKETT'S MASTERPIECE

Impressed by the way of life of the Amish people in Ohio, Leigh Brackett sat down in 1955 and wrote a story that has been called one of the finest dystopies written in modern time. Her idea was that since the Amish people live in a simple way in the midst of modern society, they would be better equipped than others to survive in a world destroyed by a nuclear catastrophe. The result was

The Long Tomorrow, a novel that leads to an unpredictable end, actually an anticlimax, but unlike many other stories by Brackett the sense of implied existential fear and meaninglessness is not catching.

She got fine reviews. H.H. Holmes (a.k.a. no less than Anthony Boucher) wrote: "You may think you are tired of prophecies of the decay of civilization after a destructive A-war; but let me assure you that Leigh Brackett has taken this subject and made it sparkling fresh by the warmth and perception of her writing." But honestly, I cannot agree with the reviewer in the New York

Times, who found it not only "a great work of science fiction", which it is, but also "by far Leigh Brackett's best novel..."

With all due deference to

The Long Tomorrow, The Sword of Rhiannon (originally published as "Sea-Kings of Mars" in

Thrilling Wonder Stories, June 1949) is a far better novel story-wise, structure-wise, language-wise and plot-wise. In both stories Brackett describes societies that have gone down the drain, but in the latter story that spent society is used as a framework for the same society at its former height of existence, when it was teeming with life and deeds. Brackett does it in a way that strictly speaking is not new. But her way of twisting the given formula makes it completely different from other works using a similar framework. Her way of conjuring up a glorious past in contrast to a dried-up present is devastating. It is a sad hero tale that makes you think. If you are the least sensitive, this story too leaves echoes in your mind. And not to forget, it is a most entertaining story.

The hero of that masterpiece is Leigh Brackett's favorite male character. In a way, he was originally cast in that first half of "Lorelei of the Red Mist" and she developed him through a series of short stories and novels into the archetypal Brackett hero. He became Eric John Stark of many stories taking place on Venus and Mars.

With the space exploration revealing that Venus and Mars are far removed from the fantasies of planet romances, Stark ultimately left our solar system and wound up on Skaith, the dying planet of a Ginger Star. The result was the three volumes of

The Book of Skaith, pure Brackett but not really reaching the heights of

The Sword of Rhiannon, where Stark, like King Arthur, unfastens the sword and turns time upside down in an enlightening though gloomy comparative way.

INFLUENCES

With

Follow the Free Wind (1963), Brackett did for the western story what she did for the Hawks/Wayne co-operation. It is a Western based on the life of James Beckworth. The novel won her "The Spur Award" from Western Writers of America. It is a captivating novel from the very beginning and when reading it, the story seems to have been written in one single burst of creativity. It once more shows the literary diversity of this woman talented far beyond mere talent. (To mention a curiosity, she was the ghostwriter behind George Sanders' novel

Stranger at Home.)

John Clute is absolutely right when he states that Leigh Brackett "was a marked influence upon the next generation of writers." In many respects, she was a writer's writer from the very beginning. Ray Bradbury has told us that she was his best loving friend and teacher and he her best loving friend and student.

For three years, 1941 to 1944, they met every Sunday at Muscle Beach in Santa Monica. "I would bring along a new short story (dreadful) and she would let me see one of her

Planet novel chapters (beautiful) and I would praise hers and she would kick hell out of me and I'd go home and rewrite my imitation of Leigh Brackett."

Marion Zimmer Bradley talks about how influenced she was by her. It has been said that E.C. Tubb could quote Brackett by heart. Michael Moorcock has said that Brackett and not Moorcock "should really be collecting the Elric royalties." Reason: "Anyone who thinks they're pinching one of my ideas is probably pinching one of hers." Moorcock also thinks that with "Catherine Moore, Judith Merril and Cele Goldsmith, Leigh Brackett is one of the true godmothers of the New Wave." He even makes the statement that Brackett antedated cyberpunk by fifty years! Well, well. It may be a little bit difficult to digest, but perhaps Moorcock knows something, I can't say.

The list of writers paying tribute to her includes many other names like Philip José Farmer and Andre Norton to mention a few. Furthermore, she has been favorably compared to Graham Greene, James M. Cain, Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Edgar Rice Burroughs. And mystery writer Michael Connelly "blames" her for saving him from a life in construction work through her screen adaptation of Chandler's

The Long Goodbye.

STAR WARS AND THE END

At the end of her life, Leigh Brackett's tryst with space opera came full circle at the same time as she was given another opportunity to make her point in defending her beloved genre. She was assigned to write the screen-script for the second

Star Wars movie, Episode Five,

The Empire Strikes Back, based on George Lucas' idea, thus combining her skill at space opera with her skill as a scriptwriter.

With

Star Wars (1977), George Lucas had launched the first believable space opera movie. Thanks to technological breakthrough, the laughable attempts in the past (remember Flash Gordon and similar efforts?) were surpassed and the space opera triumphed on the silver screen. Lucas was inspired by everything from Buck Rogers on, and he combined the many loose ends into a reasonably good space adventure where some of the best qualities of the genre were emphasized. And it all ended like an ancient Greek tragedy with an Oedipal twist.

Leigh Brackett was well aware of the rules when assigned a job within the movie- and TV-industries. "If you want to do something on your own, fine," she told me. "Write a book or try to sell one of your own ideas and stories and pilots, but in the industry, when you get an assignment and work for other people, you have to adjust and rewrite and/or be rewritten over and over and over again. And you know that when it comes to the sticking-point, there is no guarantee that the movie or the TV-play will ever be produced at all."

In 1977, she wrote the first draft for

Star Wars: Episode Five, the Empire Strikes Back, delivered it to the 20th Century Fox studios and – died! The day before she died in 1978 she called Ray Bradbury and told him laughingly that her doctor "had injected a huge overdose of painkilling drugs so that she would die joyfully."

Posthumously, she was awarded a Hugo for her

Star Wars script. As Jerry Weist puts it: "Jedi Master Yoda is pure Brackett." Well, Lawrence Kasdan also had a finger in George Lucas' pie. Anyhow, it is not an exaggeration to state that of all the six

Star Wars movies,

The Empire Strikes Back is by far the best one. Who knows? Maybe we can credit that to Leigh Brackett?

I am quite sure that the feeling Mr Darcy gives utterance to when he, in a first attempt, proposes to Miss Elizabeth Bennet in Jane Austen's

Pride and Prejudice, that the same feeling is shared by some of us readers when it comes to Leigh Brackett's best stories:

We ardently admire and love them!

* * *

Bertil Falk (born 1933) is a well-known Swedish journalist and author with a wide scope of interests, especially fond of crime, science fiction and horror/fantasy. His short stories have been published in, for example,

Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine. Read his bio

here.